ADDRESSING THE LOW SELF-ESTEEM ALLEGATIONS

Dealing with the fallout from the headless biker's miraculous recovery. . .

Last time, linked below, it was revealed that our cyclist friend (over whose demise we lost so much sleep) was far less decapitated—and therefore far less dead—than first thought:

But not all of the fallout from his resurrection was good . . .

It was also revealed to us (and by “us,” I’m referring to anyone who witnesses any sort of Looney Tunes-esque mishap/accident like this one) that our tendency to laugh/snicker/giggle uncontrollably in such moments is actually cause for concern. It’s proof, you see, that we have Low Self-Esteem.

A real boot-in-the-teeth. And a particularly steel-toed one, given who’d delivered it: Wikipedia, who’d always been such a loyal steed for us over the years—so it’s fair to say our friendship’s on the rocks.

Obviously, we immediately set off to prove Wikipedius, the Filthy Backstabber wrong; to find some justification for our behavior that made no mention of our self-esteem.

We learned that the drivers for this phenomenon (called “Schadenfreude,” wherein we take pleasure in others’ misfortune) are, apparently, “rivalry,” “aggression,” and “justice.” We then set about trying to figure out which of those had been at play in this incident. It wasn’t obvious, since I’d never met the poor guy, nor even seen him until after the accident, so that more or less ruled out “rivalry” and “aggression.” In a way, this was good news, because “justice” happened to be the most noble-sounding of the three. (From what I could tell, the more “justice” had been served, the more “enjoyment” we were allowed to derive, morally speaking. . . Or something like that.) But what “justice” had been served? The punishment—i.e., his near-decapitation—couldn’t possibly have been deserved, unless he’d done something seriously wrong.

After some thought, though, it hit me: he had . . in the view of my subconscious, at least. It turned out that any “pleasure” I’d taken in the cyclist’s misfortune was not caused by any lack of self-esteem, but instead by long-repressed trauma. That’s right. I—not the cyclist—was the victim here. Allow me to explain . . .

Here’s what happened. As I stewed over everything that evening, I remembered that a few nights earlier I’d watched the new documentary ESPN had released (in their “30-for-30” series) . . . which was about none other than Lance “LiveStrong™” ArmStrong.

For anyone unfamiliar, Armstrong was a cyclist who’d been a pillar of American culture in the early 2000s (my formative years—which will become relevant). He’d inspired millions by beating cancer and going on to win the Tour de France multiple times, becoming a global superstar in the process. I was never a fan of cycling, but you didn’t have to be; he transcended the sport. He presented himself (and, in fairness, was presented by the media) as a superhero, representing everything that was good and pure and noble: he worked hard, he overcame adversity, he was white/from Texas, etc., etc. The total package, American Dream™-wise.

And then it all came tumbling down, when it came to light that he’d lied, bullied, and cheated his way to the top. (You might say he liked to Strong-arm. . .?) Millions of fans were left horrified, enraged, betrayed, heartbroken; he’d let us all down.

My theory is that I must have absorbed that by osmosis in my young/impressionable state. So—as I build my case here—that’s the wider cultural context for you.

The other connection, which I’d been reminded of by the documentary, was even more personal. Get this: growing up, I was pretty much neighbors with Lance’s nemesis, a guy named Floyd Landis. He’d won the Tour de France in 2006, but then took the fall for doping, letting Lance get away with it. After serving his suspension, Landis expected a thank you/welcome back into the team, but found himself iced out, with his teammate Lance showing him no loyalty/gratitude. As you can imagine, this rubbed our buddy Floyd (as a Mennonite/man of principle, etc.) the wrong way, and so he decided to blow the whistle on the whole thing, which led to Armstrong being taken down.

Full disclosure, Floyd and I weren’t actual neighbors, only “spiritual” ones, he was from a town just a couple miles away back in central PA. But, still, one time, when I was a kid (it must have been before the doping controversy and his subsequent retirement, so between 2002-’05) my mom and I saw him on a training ride one on one of the wooded, winding roads which cover so much of the region. (He didn’t wave to us as we drove past, or anything, but I don’t hold that against him. Safety first.)

Point being: blood’s thicker than water, and so my loyalties lie with Floyd, my Amish-country brother. So, in solidarity, I’ll always have a bad taste in my mouth when it comes to Armstrong, the International Cycling Federation, and any other relevant parties. (We’ll throw in cyclists in general, just to be safe.) Oh—and, last but certainly not least, the iconic yellow jersey, the one that our good friend Floyd had had ripped away, and the one that Lance had been allowed to desecrate for so many years. This, in particular, is a real sore spot. The courts can technically nullify Armstrong’s seven victories, but we all know the damage is done: whether we like it or not, his name, his likeness, is synonymous with that jersey (the maillot jaune, as it’s called in French). Just search his name on google images. I’ve been scrolling for 17 minutes, and I haven’t seen one goddamn syringe—hundreds of yellow jerseys, though, that’s for sure:

It’s like Tiger Woods with his signature “victory red” polo; these things are indivisible, inextricable. (Obviously, these marriages aren’t always for the better: like how Daniel Radcliffe will never escape being seen as Harry Potter. Or like Subway with Jared Fogle.)

At any rate, I believe this [unresolved trauma] is where my moment of “weakness” came from. The cyclist in the bright yellow jacket must’ve struck some long-forgotten nerve, leading me to believe, for a moment, that our semi-castrated nemesis had finally got his comeuppance. Obviously, this all lasted no more than a few fractions of a second, and was totally unfounded, but I think it shows just how close to the surface a lot of that trauma still is. So, if we want to blame anyone for my unsympathetic reaction, blame Lance Armstrong for scarring a generation of young people, poisoning them against cyclists—especially ones in yellow jerseys.

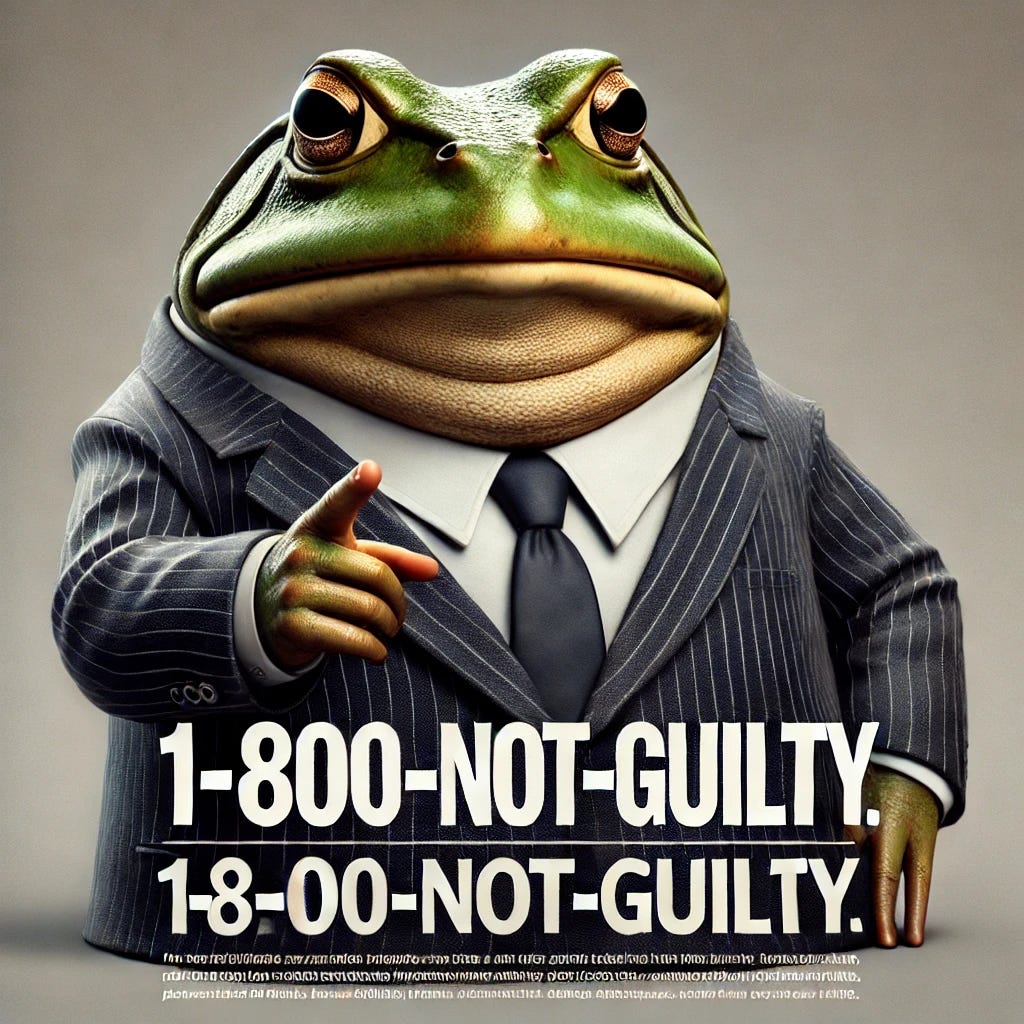

With this, I rest my case. I think our work here’s done, as far as clearing our name. We’ve at least muddied the waters. (Take that, Wikipedius, you asshole.)

For any fellow witnesses who happen to stumble in here, you’re welcome to use this “defense” if you want. (I’d strongly recommend it—it’s a real weight off.)

![Help! I've [been stabbed in the back by one of my oldest friends], and I can't get up!](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!KGXB!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F122197b7-5178-4b06-8f3a-148429a201e2_1024x1024.webp)