How the Rhino Lost His Horn: THE UNBOXING

grand reveal of my forthcoming book, available Jan 13 🤞

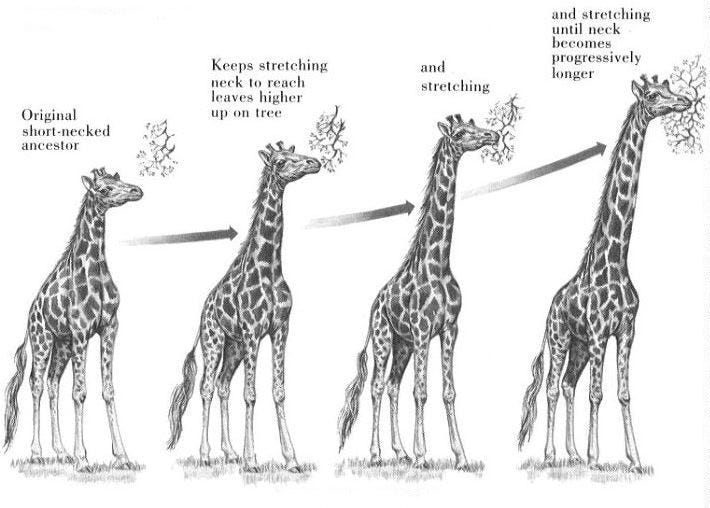

As a kid I had an old copy of Kipling’s Just So stories, which, for anyone not familiar, is a collection of little fables “explaining” how various exotic creatures came to have their unique traits. The premise for these is a kind of pre-/anti-Darwinian theory of evolution called Lamarckism, which claims that creatures acquire/“learn” their adaptations after birth and then pass them down to their children. The classic example being the giraffe, which (according to the theory) once had short necks and were basically horses, but then the short trees all died out or whatever and so they had to streeeetch their necks to reach the higher branches for fruit; the ones who were able to do this passed those traits down.

As it happens, one of the Just So stories explains how the rhino came to have all that excess skin. I won’t spoil it, but it involves him being pranked while he was busy swimming on a hot day (he’d left his skin-suit, hitherto snug-fitting, onshore).

And so the title was a shout-out to those stories, which have, I’m sure, captured the imagination of countless kids over the last century or so, inspiring them to take an interest in wildlife and nature and to dream about maybe seeing these creatures some day, and even heading off to the far corners of the world to see them in their natural habitats.

There is of course the colonial/imperialist context/elephant-in-the-room here, re: Kipling and his contemporaries, but this is so inextricable from South Africa’s history and present (as well as that of the whole region) that I think it’s fitting to reference it. (And I do go on to address all this in the book.) I wanted to put a darker twist on those old, ostensibly virtuous notions, of expansion and “discovery”; the self-bestowed “burden” Westerners had to bring enlightenment and civilization to these backwards places, with their strange animals and people.

I wanted to hint that we may need an updated version of the old stories we told ourselves about the world, now that we actually have a grasp on the impact we’ve had. Our relationship with these “exotic” places aren’t as. . . mutually beneficial as we might have been led to believe in. We’ve inflicted untold damage on natural habitats, animal migration patterns, local populations (both human and not) over the centuries.

Despite Lamarckism being debunked, though, I think we’ll always gravitate toward it (when it suits, at least). Something about that line of thinking just resonates. There’s consolation, I think, in believing that we’re in control of our own destinies, that we are more than just one tiny, predetermined link in a chain; that our decisions matter, that we are unique, sovereign actors.

Sure enough, we’ve spent untold hours/dollars/lives in our attempts to play god — a position for which we are uniquely unqualified — with all sorts of things over the years, genetically modifying plants and animals (and people), trying to live forever and basically trying to bend the natural world to suit us, instead of the other way around. Our human/Western exceptionalism won’t let us concede defeat. The laws of nature are there to be broken. That shit may apply to squirrels or fruit flies or whatever, but not us.

So, in that way, Just So stories, silly little children’s stories though they may ostensibly be, are right up our alley. We love the idea that an individual could break free from the herd and change the course of a species’ history. This sort of myth-making, wherein we believe that our [positive] traits, such as our wealth, our success, our work-ethic, our cunning, are a product of our decisions, and nobody else’s, is irresistible. This feels especially apposite to our Westernized, “highly-advanced”, digital Silicon Valley-technocract-driven; the world of the gig/hustle/grindset economy, of every man for himself. Our economic system, and thus the culture and society we’ve built around it, is predicated on the notion that the individual is ultimately responsible for any successes and/or failures that occur in the course of their lives; “there is no such thing as society”, you’re on your own.

Of course, the flip-side to all this is particularly dangerous, as it means that we can pretty easily be talked into believing that anyone suffering is doing so due to their own poor decisions, and thus deserves to suffer. The other corollary here, of believing that we are not beholden to the past, that we are separate and above the natural world, is that we owe the planet nothing. And these are both some pretty slippery slopes — that we’re already well on our way down.

So I explore these themes throughout the book: whether this is the way things have to be, whether this is the natural, inevitable state of things, i.e., that we don’t have an obligation to each other, to future generations, or to those that aren’t our direct offspring.

I also wanted to nod to the unenviable task of trying to tackle problems in a world where the challenges we face are so interconnected. It’s akin to playing a cross between Whac-a-Mole and Operation: our every action — however well-meaning! — can and will have unintended consequences, and can often completely fail to address the root issue, or even exacerbate it. I.e., even if we’ve “solved” the problem for the rhino (how generous of us!) by sanding away its horn, we ought not hang up the “Mission Accomplished!” banners just yet. The work has only just begun. This all applies to my involvement, too: Why is it that kids like me love going off to the third world to “save the children”? Have I actually made a difference? Even if I have, has the benefit been canceled out by the fact that I just gave a bunch of money to a potentially corrupt NGO? These are the sorts of questions we’ve now got to think about, and that persist throughout the book (not that I can guarantee any satisfactory answers!): What it means to be an ethical citizen, traveler, environmentalist, altruist. What our obligation is to these places around the world.

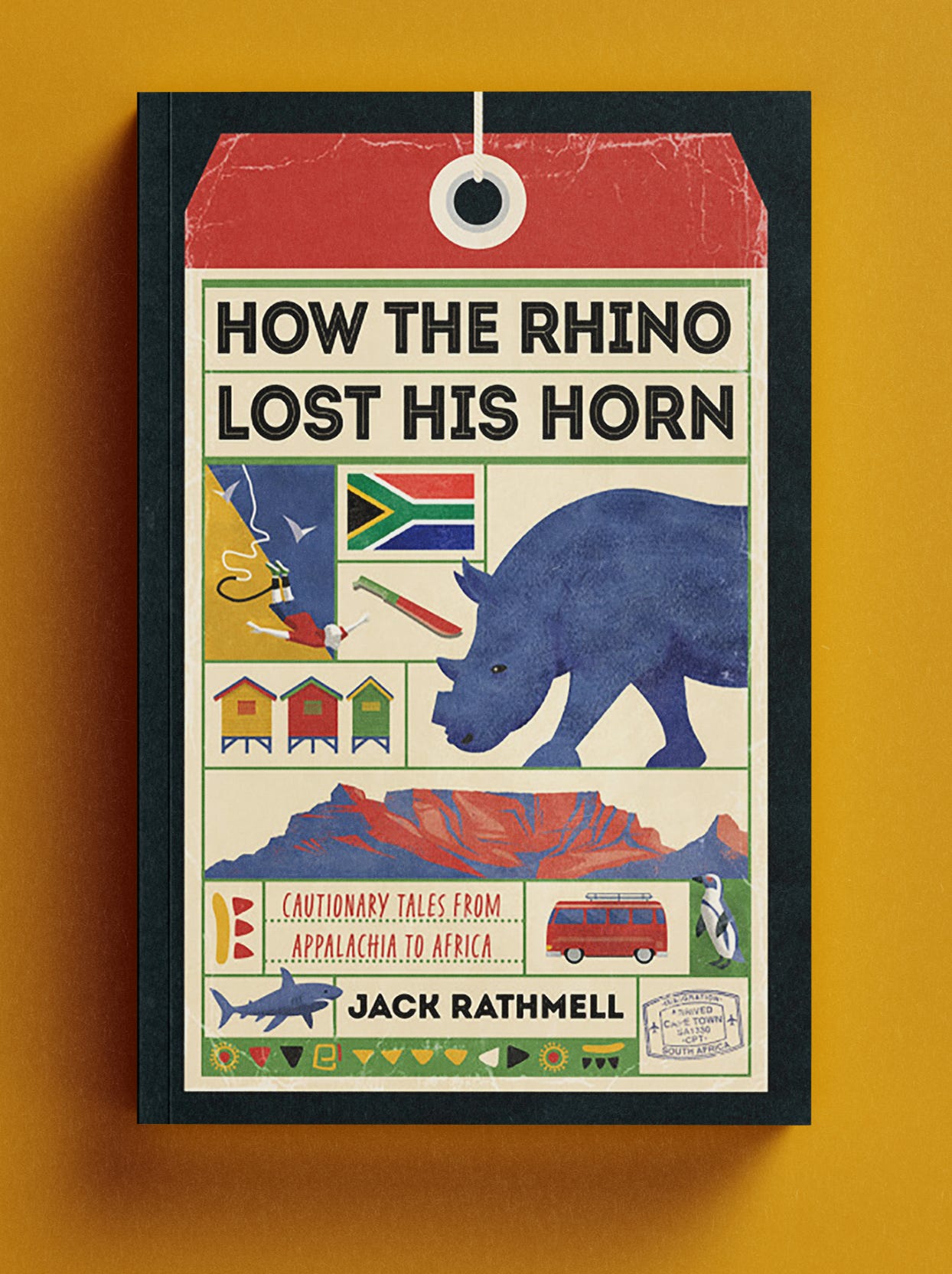

As far as the art, I worked with a really good graphic designer, Ed Simkins. In the end we had much less time to do it than I would have liked. (Admittedly, sometimes a time constraint is actually a good thing; you can get so caught up in perfectionism, tweaking things back and forth, that you never let things go otherwise.) Before he was brought in to rescue things, suffice to say things were. . . not looking good. That’s a funny story that I will share once the book is out.

Anyway, I think it does a nice job of capturing the spirit of the book. I wanted it to be kind of multi-varied and unorthodox and patchwork, to let the reader know that it might not be this perfectly streamlined, neat-and-tidy, boilerplate coming-of-age story. South Africa’s not that kind of place, those aren’t the times we’re living in, and I’m not that kind of person/writer (not in this story, at least!).

That’s all for now. The book will be coming out on January 13; there will be a pre-order link available soon. (I’ll send another post out when that’s ready, and I’ll also update this post to include it.) Remember to subscribe and share ( ͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)